Biennial Fantasy

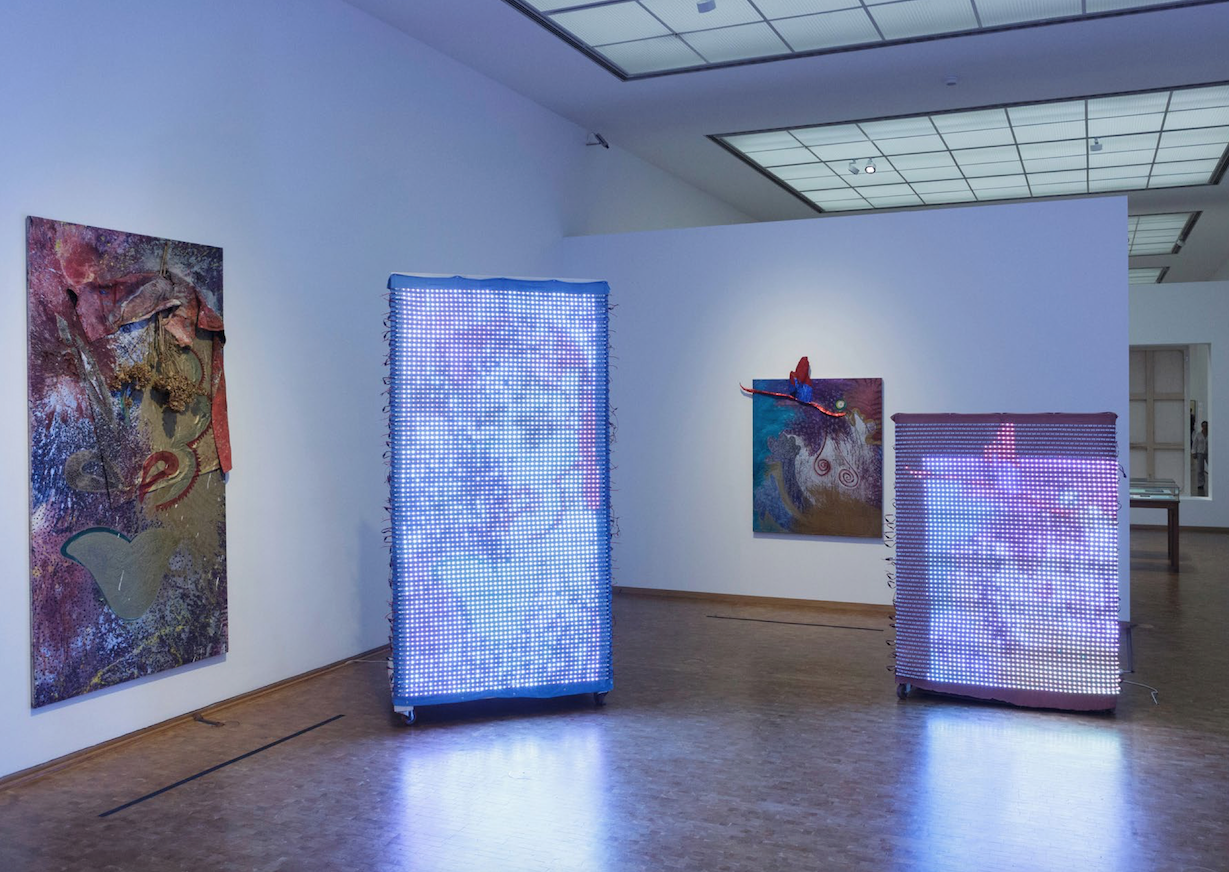

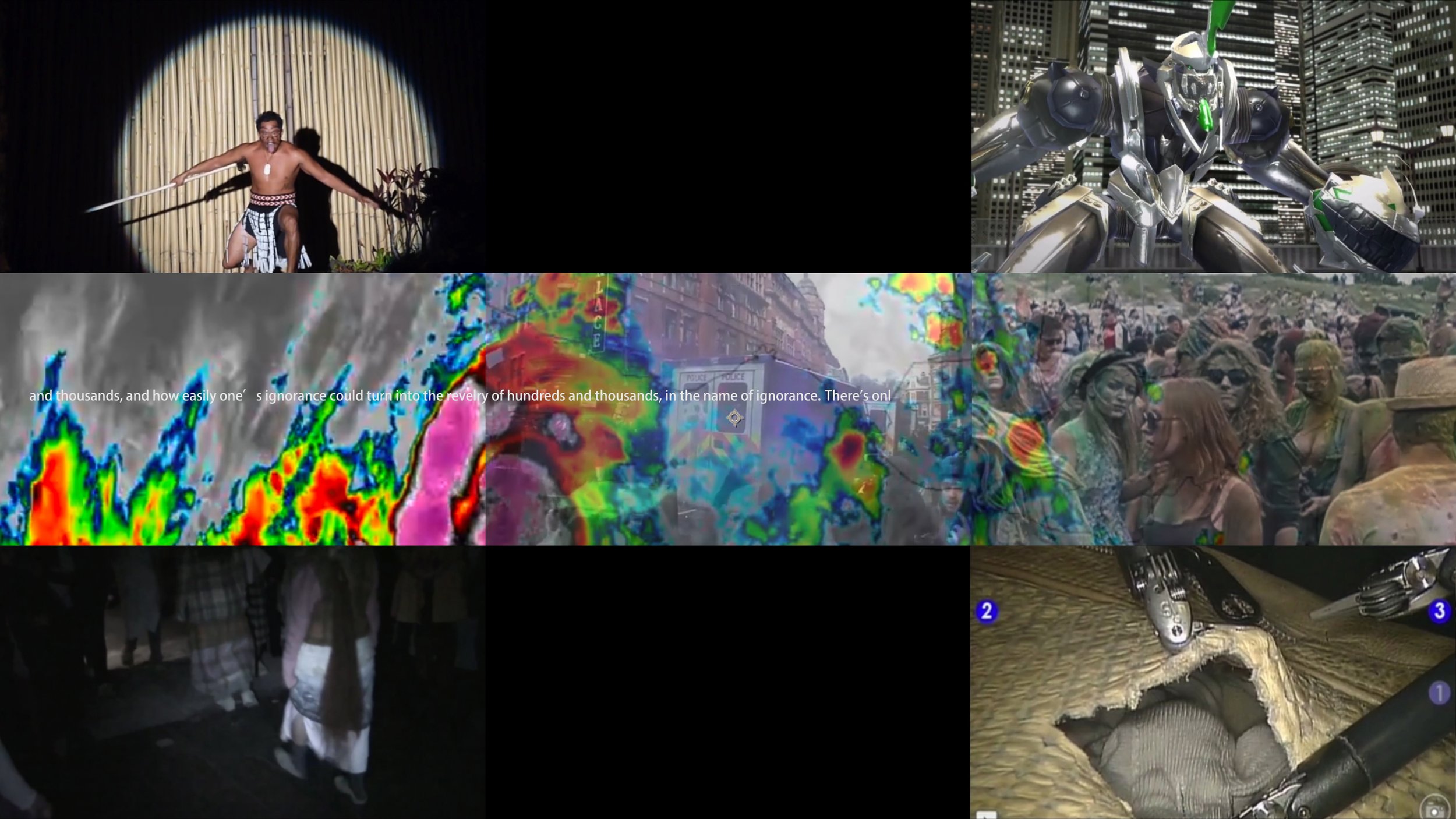

At Ward Center, in the space that was a famous footwear emporium, is a multi-sensory experience that runs from Chiharu Shiota’s mind-boggling environment created from thousands of intricately woven threads to Bougainville artist Taloi Havini’s video exploration of the legacy of mineral extraction in the pacific.

Across town in Bishop Museum, Hawai‘i-raised, New York–based Paul Pfeiffer has created an installation that centers on the portrait of four-year-old Prince Albert Edward Kaleiopapa-a-Kamehameha. Through May 2, Honolulu is a contemporary art hot spot as the second Honolulu Biennial takes up residency at more than 10 locations—indoors and out—throughout the city.

In a town where major cultural events such as the Hawaii International Film Festival and the Hawai‘i Food & Wine Festival leverage Hawai‘i’s geographical location to put an emphasis on the Pacific Rim, the Honolulu Biennial is no different. And its focus on the expansive region’s indigenous perspectives—from Papua New Guinea to the Pacific North- west—make it a one-of-a kind art event, for participants and viewers alike.

Co-founded by independent curator Isabella Hughes and international recruiter Katherine Tuider when they were still in their twenties, the Honolulu Biennial was met with some resistance and skepticism in the Hawai‘i arts community when the pair began planning in 2014. It was a scramble to complete the debut biennial’s primary venue, The Hub (the former Sports Authority transformed into a stylish blond-wood space by installation designer Scott Lawrimore), in time for the March 2017 opening. But when its doors, guarded by a giant, pink winged pig by Choi Jeong Hwa, opened, it was clear the duo—with a team of volunteers running on fumes—had pulled off an incredible feat.

They secured the highly respected director of Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum Fumio Nanjo as curatorial director, showed a knack for cultivating sponsors and donors such as Howard Hughes Corp. and Taiji Terasaki, welcomed Maori art historian and artist Ngahiraka Mason as curator, had some of the most exciting names in contemporary art on their roster of 30 artists, earned international press and threw one hell of an opening party.

And when it was over, they immediately started planning the next one. Two years later, Tuider is executive director, with Hughes moving to the board, allowing her to focus on her growing family business Shaka Tea, and the biennial is back bigger and better. At the curatorial helm is Nina Tonga, curator of Pacific art at the storied Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Called To make Wrong | Right | Now, the second Honolulu Biennial presents 74 works—31 of them new site-specific commissions—by 47 artists. From names that have only been seen in small local shows to stars whose work is in the Tate Collection and has been shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the participating artists’ work makes for hours of exploration, introspection, education, puzzlement and wonder.

The title refers to the last lines of Manifesto, a poem by the participating Native Hawaiian artist and poet Imaikalani Kalahele. In a world of colonial misdeeds, it is an appeal for justice through the recovery of histories and reaffirmation of ancestral connections. The biennial is all about connecting dots, and the curatorial team has used the metaphor of the ‘aha, or cordage, in the way they work, connecting times and places, and the passing down of knowledge through the generations. They also knot together the artists’ diverse practices. And in the end, it the artists who drive what the biennial is about.

“What we wanted to do in terms of a curatorial approach is to allow our artists to guide us on what is important in this region,” says Tonga. “We’ve tried to be open to the connection between what the artists are doing, so the way colonialism comes through in the work is a gauge of what’s happening in the Pacific.”

The Honolulu Biennial isn’t the only art event focused on the Pacific or on indigenous artists—there is the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art organized by the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, Australia; the Contemporary Native Art Biennial in Montreal, Canada; and next year the Winnipeg Art Gallery in Canada will launch its Winnipeg Indigenous Biennial. What sets the Honolulu Biennial apart is its independence from an institution.

“Curators at other institutions, myself included, see the value in the Honolulu Biennial being autonomous—not being generated inhouse at any particular institution,” says Healoha Johnston, director of curatorial affairs, and curator, arts of Hawai‘i, Oceania, Africa and the Americas at the Honolulu Museum of Art. “It creates a lot of freedom in terms of the vision, it also creates a very fresh flow, so year after year there are different curators contributing to it. I think that’s going to keep it very dynamic and really exciting.”

The biennial is a cultural glue binding Honolulu’s institutions in a celebration of contemporary art. At the Bishop Museum, works by Paul Pfeiffer, James Bamba, Bruna Stude and Ho‘oulu ‘Aina Artist Collective have found homes on the sprawling campus. Bernice Akamine’s epic installation Kalo, five years in the making, is planted at Ali‘iolani Hale, where the declaration of the Provisional Government that marked the over- throw of the Hawaiian monarchy was read in 1893. Foster Botanical Garden, the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, YWCA Laniakea and multiple sites in Chinatown are also venue partners.

The Honolulu Museum of Art has devoted to the biennial its entire contemporary gallery, where a four works create an energetic dialog. Alaska-based Tlingit-Aleut artist Nicholas Galanin’s work, We Dreamt Deaf, stops visitors in their tracks. A polar bear is trying to drag itself forward with its two front plate-size paws as his hindquarters melt away, like its environment. “The artist knew the hunter who killed the bear, and where it was shot,” says Johnston, explaining that the animal had been turned into a rug, and Galanin bought it and had a taxidermist work on it.

“What Nicholas is getting at is this idea between exploitation or conservation of the land, and that is a complete imbalance,” says Johnston. “The natural world cannot sustain that kind of approach.” She especially values the way the work “resonates closely with the way Hawaiians think about land—you make measured decisions so that you are conserving when you need to conserve, and you are conserving what you need to conserve so something is brought back to health.”

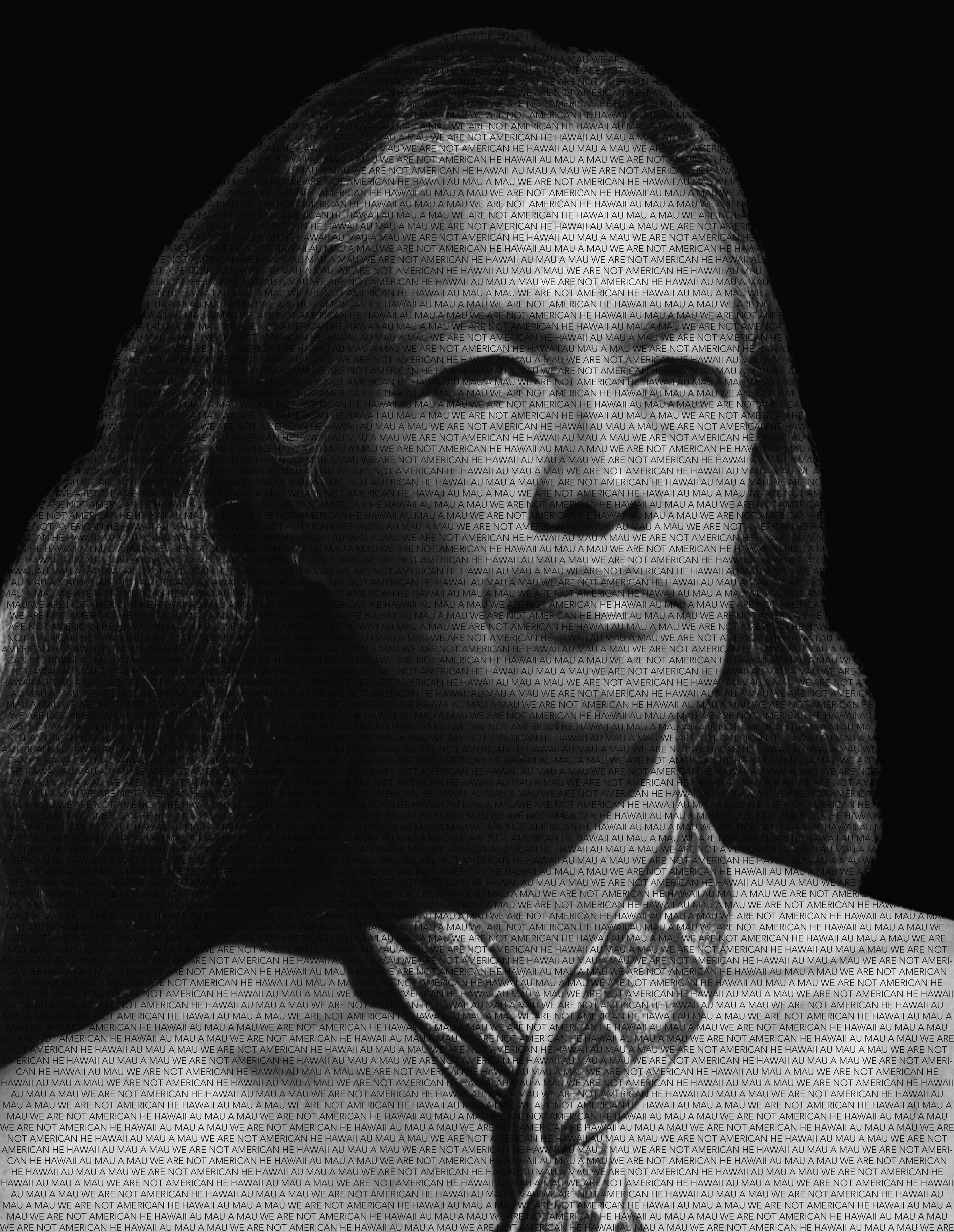

Accompanying the bear are three works that echo Galanin’s message in different ways—a video installation by native arts collective Postcommodity that depicts a young woman butchering an animal in a hotel bathtub; an installation by Portland-based native artist Marie Watt using her signature wool blankets that were stitched with text from Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” by a sewing circle of local participants at the museum in January; and Kapulani Landgraf’s massive photo project, ‘Au‘a, comprised of 108 portraits of people (like activist Walter Ritte) the Native Hawaiian artist selected as someone who has contributed to a collective good.

Three weeks before the opening of HB19, 2,200 children were already signed up for free field trips to The Hub, Foster Botanical Garden and the “downtown loop,” part of the biennial’s rich public programming. And Tuider is giddy about it. “We basically shut down The Hub on Wednesdays for the kids,” she says proudly.

Without Howard Hughes Corp.’s support as founding sponsor—giving the biennial a physical center—”we wouldn’t be able to do what we do,” says Tuider.

And she hopes their contributions set an example for other businesses to “support our community and the arts and see how having a healthy arts community benefits them. I also hope it creates more opportunities for public funding to step up and support local nonprofits.”

The biennial isn’t just about looking. A stage in The Hub is open to anyone who is part of the arts community to perform for free, no matter the medium or discipline. “It’s a way to make sure the biennial is of this place and foremost for the people who live here. At the same time, visitors can have a one-of-a-kind experience—the majority of artworks are new commissions of Hawai‘i or inspired by this place. They can’t see these works anywhere else.”

What Johnston especially likes about HB19 is the way “the preconceived definitions of art are dissolved,” she says. “So you have artists who in some ways don’t even necessarily identify as artists, but who are practitioners who create artful work, and the curators look at them and say, ‘Of course they are artists, of course this type of visual production or contribution to one’s own community has a place in the art world.’ There’s a huge range of work and that’s exciting. It is a good opportunity for the emerging artists, but it’s also just good for people to rethink basic assumptions about ‘What is art?’”